Access to health care for undocumented immigrants in the U.S. is shaped by several policies and programs at the federal state and local level. This issue brief provides an overview of key federal and state policies.

Are undocumented immigrants eligible for public insurance programs?

With the exception of emergency medical care, undocumented immigrants are not eligible for federally funded public health insurance programs, including Medicare, Medicaid and the Child Health Insurance Program (CHIP).1Medicare is a social insurance program that provides health insurance to people age 65 and over, as well as people with permanent disabilities and end-stage renal disease. Medicaid is a means-tested social welfare program that provides health insurance to certain categories of poor people. CHIP, created in 1997, is a block grant program to expand coverage to children in families with incomes that exceed Medicaid eligibility.2 There is no organized, national program to provide health care for undocumented children. U.S.-born children in mixed-status families may be eligible for Medicaid or CHIP if they qualify on the basis of income and age.

Although federal funds may not be used to provide non-emergency health care to undocumented immigrants, some states and local governments use their own funds to offer coverage to undocumented children.3 For example, the Healthy Kids program in San Francisco covers uninsured children under the age of 19, including undocumented children.4 Similarly, the All Kids program Illinois covers all children under the age of 19 who meet program income requirements, regardless of immigration status.5

PRUCOL (Permanent Residence Under Color of Law) is a public benefits eligibility category that refers to individuals who are in the U.S. with the knowledge of immigration services and are not likely to be deported.Before the adoption of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996,6 people with PRUCOL status were eligible for Medicaid, but PRWORA eliminated their eligibility with the exception of emergency services. In New York, the State Court of Appeals (Aliessa et al. v. Novello) concluded that denying access to Medicaid violated the equal protection clauses of the New York and U.S. constitutions. As a result, New York provides Medicaid to this population using state funds only.

In about half of the U.S. states, immigrant children under the age of 21 and pregnant woman who have been granted deferred action on their immigration status are allowed to apply for Medicaid and the CHIP or enroll in their state’s high risk insurance pool. An exception to this, however, are the so-called “dreamers” – the estimated 1.7 million undocumented teenagers and young adults granted deferred action by the Obama Administration on June 15, 2012.7 President Obama announced that undocumented immigrants who were brought to the U.S. before they turned 16 and are younger than 30, have been in the country for at least five continuous years, have no criminal history, graduated from a U.S. high school or earned their GED, or honorably discharged from the military will be immune from deportation and can apply for a work permit that will be good for two years with no limits on renewal.On August 28, 2012, the Obama Administration announced that the young people affected by this directive would not meet the definition of being “lawfully present”and would therefore be ineligible for Medicaid, the CHIP and the insurance benefits of the ACA.8

How is emergency medical care available to undocumented immigrants?

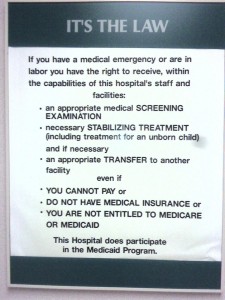

In 1986 the Congress enacted the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) as part of the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA) (Pub. L. 99–272). The law was designed to provide patients with access to emergency medical care and to prevent hospitals from “dumping” unstable patients that could not afford to pay for their care.”9 Under the law, “any patient arriving at an Emergency Department (ED) in a hospital that participates in the Medicare program must be given an initial screening, and if found to be in need of emergency treatment (or in active labor), must be treated until stable.”10 The law defines an emergency medical condition as a “medical condition manifesting itself by acute symptoms of sufficient severity such that the absence of immediate medical attention could reasonably be expected to result in – (i) [p]lacing the health of the individual … in serious jeopardy; (ii) [s]erious impairment to bodily functions; or (iii) [s]erious dysfunction of any bodily organ part[.]” It requires hospitals covered by the law to provide patients with an emergency medical condition with “an appropriate medical screening examination within the capability of the hospital’s emergency department, including ancillary services routinely available to the emergency department, to determine whether or not an emergency medical condition (EMC) exists.” (42 C.F.R 489.24(a)(1)(i)). the medical screening examination “must be conducted by an individual(s) who is determined qualified by hospital bylaws or rules and regulations” (42 C.F.R. § 489.24(a)(1)(i)).

Although the law refers specifically to hospitals with an ED, the guidelines from the federal government have applied EMTALA requirements to all facilities that participate in the Medicare program and offer emergency services.11 Met, while EMTALA requires covered hospitals to stabilize patients with emergency medical conditions, it does not require these facilities to provide additional treatment. There is a legal dispute over whether the stabilization requirement in EMTALA continues to apply if a patient has been admitted to the hospital.12 Decisions by the Fourth, Ninth and Eleventh Circuit Courts held that hospitals have no stabilization duties once patients are admitted,13 but the Sixth Circuit held the opposite.14

Although the law refers specifically to hospitals with an ED, the guidelines from the federal government have applied EMTALA requirements to all facilities that participate in the Medicare program and offer emergency services.11 Met, while EMTALA requires covered hospitals to stabilize patients with emergency medical conditions, it does not require these facilities to provide additional treatment. There is a legal dispute over whether the stabilization requirement in EMTALA continues to apply if a patient has been admitted to the hospital.12 Decisions by the Fourth, Ninth and Eleventh Circuit Courts held that hospitals have no stabilization duties once patients are admitted,13 but the Sixth Circuit held the opposite.14

In addition to EMTALA, it is also possible for undocumented immigrants to qualify for Medicaid coverage for emergency care. The definition of emergency care and the scope of services available through the Medicaid programs vary by state. For example, in New York State Medicaid for Emergency Care may be used to provide chemotherapy and radiation therapy to undocumented patients with cancer. In New York State, California, and North Carolina, it may be used to provide outpatient dialysis to undocumented patients.15

Do undocumented immigrants have access to care through the health care safety net?

To care for the lower income residents, including undocumented immigrants, the U.S. relies on a patchwork “system” of safety-net providers, including public and not-for-profit hospitals, federally qualified community health centers (FQHCs), and migrant health centers. Since the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981, a hospital recognized as “disproportionate share hospital” (DSH) with respect to the percentages of low-income and uninsured patients it treats receives additional payments from Medicaid to support uncompensated care. Congress also required Medicare to allocate DSH funds to hospitals. The DSH programs fund hospital care for uninsured patients. Together, the Medicare and Medicaid DSH programs provide more than $20 billion to qualified hospitals annually, but these programs are scheduled to be reduced significantly under health care reform.16

Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and Migrant Health Centers are not-for-profit organizations17 funded by the federal Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). Both offer comprehensive primary care to vulnerable populations that include Medicaid patients, uninsured patients, and patients in underserved urban, suburban, and rural areas. They provide care regardless of ability to pay, insurance status or immigration status. Both are required to have a board of directors with a majority (at least 51%) of the members from the community served by the center. In addition, both types of health centers are required to use a sliding fee scale. The main difference between them is that migrant health centers are only allowed to serve migrant and seasonal farm workers and their families.*

Federal support for FQHCs increased significantly under the George W. Bush administration and they have received continued support from the Obama administration.18 Between 1996 and 2010, direct federal funding for FQHCs increased from $750 million to $2.2 billion. As of 2010, there were 1,214 FQHCs operating more than 8,000 service sites.19 In addition, there were 159 federally funded migrant health center sites, operating more than 700 service sites.20

How will the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act influence access to health care for undocumented immigrants?

The PPACA does not provide undocumented immigrants with eligibility for public insurance programs. Because undocumented immigrants are not regarded as “qualified individuals” under the law, it also does not allow undocumented immigrants to purchase health insurance through the new state health exchanges even if they are able to do so with their own money.21 Section 1312 of the Act states, “If an individual is not, or is not reasonably expected to be for the entire period for which enrollment is sought, a citizen or national of the United States or an alien lawfully present in the United States, the individual shall not be treated as a qualified individual and may not be covered under a qualified health plan in the individual market that is offered through an Exchange.”22

Despite these restrictions, the law does include additional funding for the health care safety-net, including an $11 billion increase for FQHCs and the law’s expansion of the Medicaid program may provide additional revenue to many FQHCs and other safety-net providers. Yet, the PPACA also calls for an $18 billion dollar reduction in Medicaid DSH payments and a $22 billion reduction in Medicare DSH payments through 2020. The DSH cuts are based on the assumption that hospitals will not need to provide as much charity care once the health reform is implemented. Because undocumented immigrants will not receive public or private insurance coverage under health reform, they are likely to represent a larger percentage of the nation’s uninsured population. This raises important question about future political support for the health care safety-net.23

- 1. Rayden Llano. “Immigrants and Barriers to Healthcare: Comparing Policies in the United States and the United Kingdom.” Stamford Journal of Public Health 2011. Available at: http://www.stanford.edu/group/sjph/cgi-bin/sjphsite/2011/06/immigrants-and-barriers-to-healthcare-comparing-policies-in-the-united-states-and-the-united-kingdom/.↵

- 2. Lawrence D. Brown and Michael Sparer. “Poor program’s progress: The unanticipated politics of Medicaid policy.” Health Affairs 2003; 22(1): 31.↵

- 3. S. Fremstad and L. Cox, “Covering New Americans: A Review of Federal and State Policies Related to Immigrants’ Eligibility and Access to Publicly Funded Health Insurance” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, November, 2004.↵

- 4. Available at: http://www.sfhp.org/visitors/programs/healthy_kids/do_i_qualify.aspx; accessed on February 18, 2012.↵

- 5. Available at: http://www.allkids.com/hfs8269.html; accessed on February 18, 2012.↵

- 6. 62 Fed. Reg. 61344, November 17, 1997.↵

- 7. National Immigration Law Center. “FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS: Exclusion of People Granted “Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals” from Affordable Health Care,” Washington DC: National Immigration Law Center, September 20, 2012 Available at: http://www.nilc.org/FAQdeferredactionyouth.html.↵

- 8. Robert Pear, “Limits Placed on Immigrants in Health Law,” New York Times, September 18, 2012; A1.↵

- 9. Joseph Zibulewsky. “The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA): what it is and what it means for physicians.” Proc Bayl Univ Med Cent 2001 October; 14(4): 339–346.↵

- 10. 42 U.S.C. § 1395dd↵

- 11. Zibulewsky: 342.↵

- 12. Edward C. Liu. EMTALA: Access to Emergency Medical Care. CRS Report for Congress, July 2010.↵

- 13. Bryan v. Rectors & Visitors of the Univ. of Virginia, 95 F.3d 349, 352 (4th Cir. 1996), Bryant v. Adventist Health Sys., 289 F.3d 1162, 1168–1169 (9th Cir. 2002), Harry v. Marchant, 291 F.3d 767 (11th Cir. 2002).↵

- 14. Thornton v. Southwest Detroit Hosp., 895 F.2d 1131, 1135 (6th Cir. 1990).↵

- 15. Nina Bernstein, “For Illegal Resident, Line is Drawn at Transplant,” New York Times December 21, 2011: A1.↵

- 16. Michael K. Gusmano and Frank Thompson. 2012. “The Safety Net At The Crossroads? Whither Medicaid DSH,” Chapter 7 in The Health Care Safety-Net and Universal Coverage. Edited by Mark Hall and Sara Rosenbaum. Rutgers University Press, forthcoming.↵

- 17. Some of the migrant health centers are operated by state and local health departments.↵

- * According to the Health Resources and Services Administration, “Principal employment for both migrant and seasonal workers must be in agriculture (ht;://bphc.hrsa.gov/about/specialpopulations/; accessed on March 15, 2012)↵

- 18. Aaron Katz, Laurie E. Felland, Ian Hill, Lucy B. Stark. “A Long and Winding Road: Federally Qualified Health Centers, Community Variation and Prospects Under Reform.” HSC Research Brief No. 21, November 2011.↵

- 19. http://www.statehealthfacts.org/profileind.jsp?ind=424&cat=8&rgn=1; accessed on February 19, 2012.↵

- 20. http://www.ncfh.org/?sid=37; accessed on February 19, 2012.↵

- 21. Timothy Stoltzfus Jost. Health Insurance Exchanges and the Affordable Care Act: Eight Difficult Issues. The Commonwealth Fund, September 2010.↵

- 22. § 1312 (f) (3).↵

- 23. Mark A. Hall. “Rethinking Safety-Net Access for the Uninsured.” NEJM 364;1: 7–9.↵